Feel free to share this image with anyone!

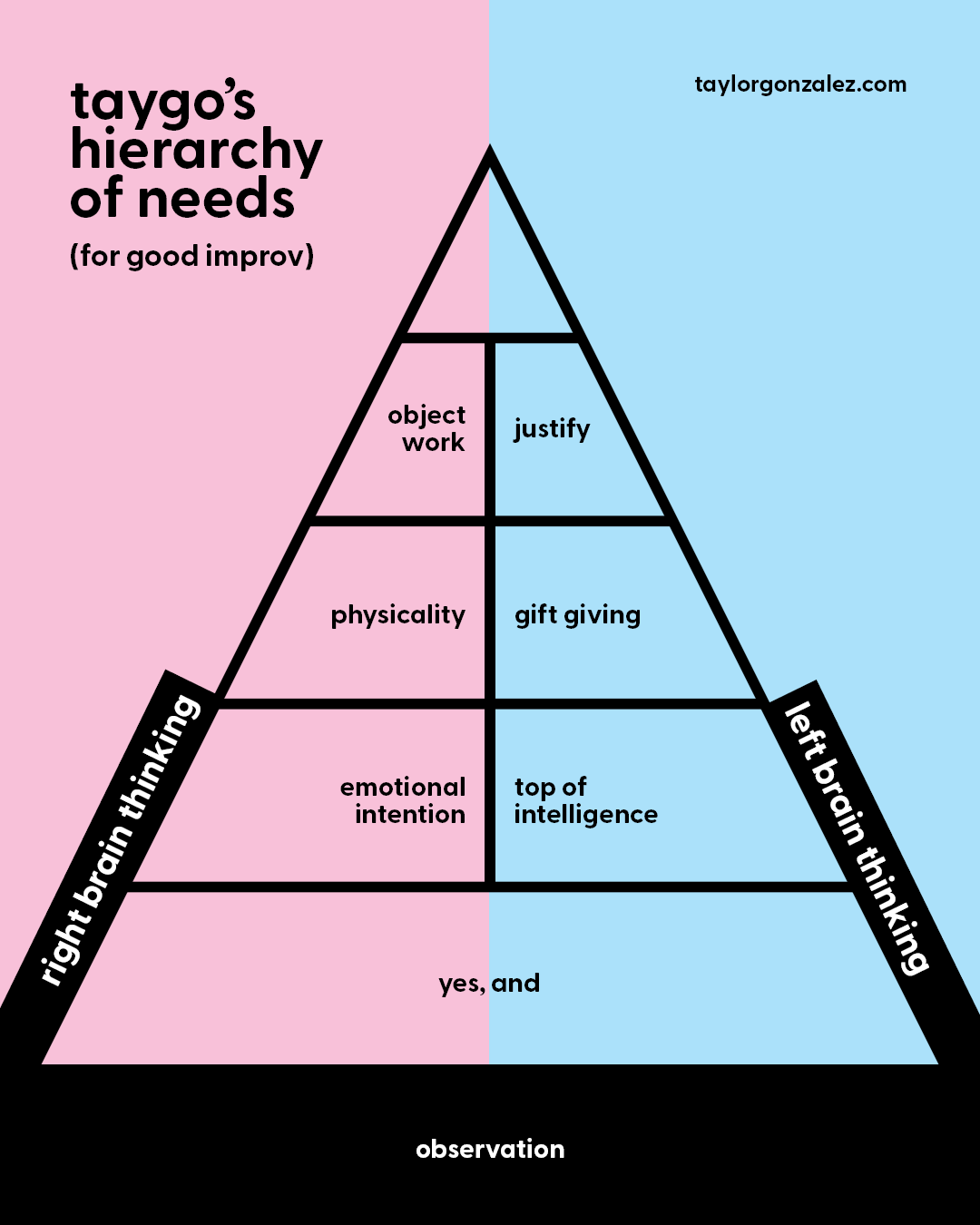

Introduction to the Pyramid

After studying and teaching improv for many years, I became more and more infatuated with the idea that a typical improv scene has prioritized “needs” not unlike the concept of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. This template helped me organize the most basic (and important) “tools” on our “tool belt” when doing improv. These building blocks not only make scenes better and more fun, but they also make improv much easier for the players involved.

Observation.

Observation represents the soil or foundation underneath the pyramid because we can’t even begin to “yes, and” our scene partner properly unless we’re hyper observant of everything they do. “Observation” in this context is defined as a combination of (a) intense listening to what our partner is saying and (b) keen observation of their nonverbal cues, such as body language and object work. If we’re not observing close enough, we risk not agreeing to our partner’s true idea, which may be hidden in the subtext or body language of their moves.

Yes, And.

The concept of “Yes, And” is the most primitive need for an improviser. It’s impossible to improvise without mainlining this mantra directly into your bloodstream. These two simple words represent the two critical steps that should precede anything and everything an improviser will do in any given scene or show. “Yes” represents 150% acceptance of your partner's idea, regardless of whether you understand it or not. It’s the funniest thing you’ve ever heard, and you want to support it wholeheartedly. But it’s not enough to just agree with your partner, you also want to supplement their idea with your own: the “And” represents your contribution to your partner’s idea. The addition should be directly correlated to their idea and not something completely out of left field.

Emotional Intention.

Emotional choices add life and energy to scenes while also being very relatable to the audience. People may not understand what’s happening in your scene, but they’ll stick with you if they understand how you feel. Interesting emotions also lead to interesting behavior. We never want to play characters who are neutral, uninterested, disengaged, or “chill,” because these people will not be inclined to do anything interesting. Why would they? Our characters should always be emotionally invested in whatever’s happening in the scene.

Playing to the Top of Your Intelligence.

This has nothing to do with being smart or dumb, but simply means that you bring your entire breadth of personal knowledge into every scene you do, no matter what kind of character you’re playing. This reservoir of knowledge includes everything in your brain that you can recall: the specific things you know about, your interests, experiences, opinions, and everything in between. Utilizing this real-world knowledge in scenes adds fun color, richness, and authenticity, even if the audience has no idea what you’re talking about. If what you're saying is true and specific, it will make your scenes more fun. Conversely, playing dumb characters may be fun in the short run, but difficult in the long run because these characters cannot be scaled up and thus will end up being a burden. Not knowing things leads to questions, and questions only slow our scenes down.

Physicality.

Physicality is one of the easiest ways to make your scene more fun. It’s expressing an idea with our body instead of our words, whether it’s a funny walk, a distinct posture, or an interesting physical choice. We want to avoid “talking heads” scenes, or scenes in which the players are standing still, talking to each other without much blocking or business, because these scenes stale fast. Move around. Let your body guide you instead of your brain. Become aware of your onstage body language to ensure it’s consistent with the character you’re playing, or it could create confusion for your partner and the audience. A scene that is physical and active will always be more fun than a scene with no movement, even if the dialogue in the stagnant scene is funnier.

Gift Giving.

A “gift” is a bit of feedback or clarity that you provide to your scene partner after observing and digesting information that they provided for you. For instance, if you observe that your partner is expressing anxious body language, you might provide them with the specific reason for their anxiety. You just gave them a gift. Gifts are the currency of improv, being given and received frequently in quality scenes. Giving a gift is just about the most supportive thing you can do for your partner, save for receiving their gift with open arms and committing to it fully. Receiving a gift in a scene is a relief because now you don’t have to think anymore about what you’re doing. You can now just adopt the gift provided for you and start building upon it.

Object Work.

This is the most underrated and underused tool at our disposal in scenes. If physicality is the act of manipulating our own body to express an idea, object work is the act of manipulating imaginary things outside of our body (i.e. objects in our scenes) as if they were real props or set pieces. This not only adds richness, color, and detail to the scene, but it also helps connect our characters to the setting that we so often forget. Remember that these scenes do not take place in a white void space. And when we create an object in our scene, we should always remember that it’s there to create spatial consistency. This attention to detail adds a layer of impressiveness and subtlety to scenes.

Justification.

This is the last piece of the puzzle, the critical moment where we seize the opportunities we created by utilizing the tools listed above. By quickly and decisively deciding why we’re doing what we’re doing (or saying what we’re saying), we are creating the foundations for character deals. The why is everything. For instance, starting a scene looking very depressed is great, but it’s not quite yet a scene. It’s not until we know specifically why the character is depressed that we begin to discover the character's reasoning and personality. Once we know why a character is the way they are, it opens the door to exploring more things to do with this character. When something strange happens in a scene (which happens quite often) and it is not justified in some way, the audience gets confused and can’t follow any further without clarification. This is one of the most common ways that scenes go awry.